Japanese employs three writing systems: hiragana, katakana, and kanji.

Hiragana and katakana are syllabic scripts, each consisting of 46 basic characters representing different sounds. Hiragana is primarily used for native Japanese words, verb conjugations, and grammatical elements, while katakana is employed for foreign words, onomatopoeia, and emphasis. Kanji (every Japanese language student’s worst nightmare!), originated from Chinese characters and is logographic, representing meaning rather than sound. Kanji characters are complex and can have multiple pronunciations, allowing for nuanced expressions.

If you’re not already on top of hiragana, don’t worry – you’ll have it down perfectly by the end of your first week at Lexis Japan, and it very quickly becomes second nature to you. In fact, learning hiragana is so easy that it tends to be overlooked by students, who are much more focused on the more challenging kanji that they need to learn. This is a shame, because the history of hiragana is a fascinating journey that dates back over a thousand years. Hiragana emerged as a simplified and cursive script derived from the more complex Chinese characters, known as kanji. Let’s explore the development and evolution of hiragana throughout history.

In ancient Japan, during the 5th and 6th centuries, the Japanese language had no writing system of its own. At that time, Japan relied heavily on Chinese characters, which were primarily used for writing official documents, Buddhist scriptures, and for communication with China and Korea.

Around the 8th century, as the Japanese language and culture began to flourish independently, a need arose to represent the sounds of the spoken language more accurately. This led to the creation of two new writing systems: hiragana and katakana.

The origins of hiragana can be traced back to the “man’yōgana” system. In this system, Chinese characters were used to represent phonetic sounds rather than their original meanings. Initially, this system involved selecting specific Chinese characters that sounded similar to Japanese words. However, it was a complex and inefficient method that meant that literacy was limited to a very small scholarly class.

In the 9th century, during the Heian period, the script started to take shape as a simplified cursive text. Women of the Imperial Court, known as the “onnade,” played a crucial role in the development of hiragana. They women of the court were largely idle and had time to acquire a high level of education, something that required a writing system that was easier to use and suited the nuances of the Japanese language.

The onnade began modifying the man’yōgana characters, simplifying their shapes and emphasizing their phonetic values. This gradual transformation led to the creation of a distinct set of phonetic characters that were easier to write and more suitable for representing the Japanese language accurately.

Hiragana’s development was further influenced by the Chinese cursive script, known as “grass script” or “grass hand” (sōsho). The onnade incorporated elements of this cursive style into hiragana, resulting in its unique flowing and rounded appearance.

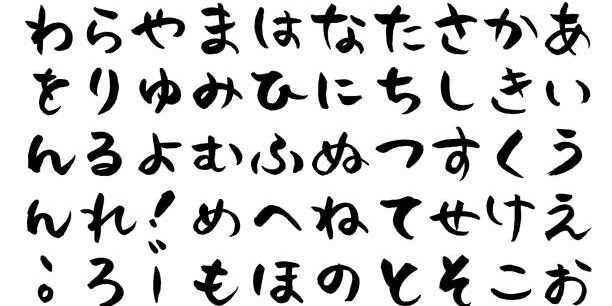

Hiragana initially consisted of about 90 different characters, which gradually decreased to the current set of 46 basic characters, known as “gojuuon,” during the 10th century. The gojuuon system organizes characters according to their syllabic sounds, starting with the five vowel sounds (a, i, u, e, o) and combining them with consonant sounds.

Throughout history, hiragana played a vital role in various literary works, particularly in the world’s first novel, “The Tale of Genji,” written by Murasaki Shikibu in the early 11th century. The novel showcased the potential and versatility of the new script.

During the medieval period, hiragana became more widely used among the general population, particularly among women who were often excluded from learning Chinese characters. It provided a means for women to express themselves through writing, promoting literacy and communication in Japanese society.

The 17th century saw the introduction of katakana, a script used primarily for transcribing foreign words and onomatopoeic expressions. However, the older script maintained its importance as the script of choice for everyday writing, poetry, and informal communication.

With the advent of modernization and Western influence in the late 19th century, there was a movement to simplify and modernize the Japanese writing system. The government introduced a series of reforms known as the “script reforms” to simplify and standardize the use of hiragana and kanji.

Today, hiragana continues to be an integral part of the Japanese writing system, alongside kanji and katakana. It is widely used for native Japanese words, verb conjugations, particles, and to provide furigana (phonetic guides) for kanji. Hiragana is taught in the first year of school, and mastering it is essential for reading and writing in Japanese. It has also become popular among non-native learners as a starting point for studying the language. The evolution of hiragana showcases the unique development of a writing system tailored to the phonetics and nuances of the Japanese language, while also reflecting the cultural and historical significance of Japan.

You’ll learn hiragana on your very first day of your Intensive Japanese course at Lexis Japan, but if you’d like to try the ’48 minute’ learning method prior to your travel, you can check it out here